June 2 – 18, 2023 | Karen Yank and Agnes Martin

Opening Reception at Turner Carroll, Friday, June 2, 5-7 pm

Opening Reception at Turner Carroll, Friday, June 2, 5-7 pm

In conjunction with the University Art Museum exhibition featuring Karen Yank and her mentor Agnes Martin, Turner Carroll is thrilled to unveil new outdoor sculptures by Karen Yank as well as wall works. Yank has had a banner year, being the recipient of the Governor’s Award for Excellence in the Arts, in addition to winning yet another public art commission and being featured in the UAM exhibition with Martin.

Work in the exhibition may be seen here.

November 29 – December 4, 2022 | Art Miami

Turner Carroll Gallery is exhibiting Hung Liu, Mildred Howard, and Swoon, at Art Miami, along with Hoss Haley, Judy Chicago, Kara Walker, and three emerging artists with current East Coast museum exhibitions who will show in Miami for the first time: Mokha Laget (Katzen Art Center), Clarence Heyward (CAM Raleigh), and Lien Truong (Nasher Museum of Art).

Turner Carroll Gallery is exhibiting Hung Liu, Mildred Howard, and Swoon, at Art Miami, along with Hoss Haley, Judy Chicago, Kara Walker, and three emerging artists with current East Coast museum exhibitions who will show in Miami for the first time: Mokha Laget (Katzen Art Center), Clarence Heyward (CAM Raleigh), and Lien Truong (Nasher Museum of Art).View artwork that will be at Art Miami here.

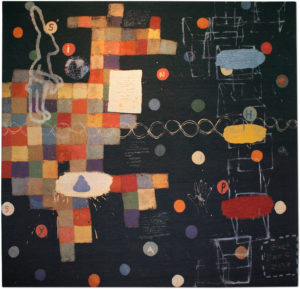

September 2 – October 2, 2022 | Karen Yank: Between Aspiration and Reality

Karen Yank: Between Aspiration and Reality, September 2 – October 2, 2022

Karen Yank: Between Aspiration and Reality, September 2 – October 2, 2022

Opening Reception Friday, September 2, 5–7pm

The circle and the cross appear thematically throughout Karen Yank’s practice. Circles can be the center of a flower, the face of a clock, a yin-yang, or a metaphor for the re-appropriation of energy through the cycles of life and death. The antitheses of her mentor, Agnes Martin’s square. In contrast, the cross can be a mathematical placeholder, a metaphor for where two forces meet, the marker for something precious, or a nonverbal sign of honesty and fidelity in the middle ages. Together the two symbols carry ancient iconographic gravity from the structure of our solar system, these cross-cultural spiritual meanings. Both powerful and metaphysical, the simple and enduring forms connect Yank’s sculptures to ancient mark-making and the human need to create.

Work in the exhibition may be viewed here.

March 5 – April 30, 2021 | Renegades

The exhibition is available on our site here.

The 3rd in a series of exhibitions treating the role women have played in art history. Opens March 5, 2021 at Turner Carroll Gallery. Titled “Renegades,” the exhibition follows two previous exhibitions titled “Can’t Lock Me Up” (2019) and “Burned: Women and Fire” (2020).

This exhibition celebrates the unveiling of the sculpture “L’implorante” by Camille Claudel, widely recognized as her most important work currently available on the international art market. Other editions of this sculpture are found in permanent collections of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Musée Camille Claudel, and others.

1864: Camille Claudel, born in 1864, has become known as one of the most important women artists ever to live. She moved mountains to pursue her art on her own terms. Camille convinced her entire family to move to Paris, so she could attend the only art academy that accepted women—L’accademia Colorrosi. She was so committed to carving her own path in the art world that even when the great artist Auguste Rodin became smitten with her skill and independence, she showed great reservation in starting a relationship with him, insisting instead that she must be her own artist, not a reflection of him. This initial indifference to his advances caused Rodin to refer to Claudel as “my fierce friend,” or my “sovereign friend.”

Eventually, when Camille Claudel decided to take part in a sexual relationship with Rodin, she declared it must be on terms she dictated. In 1886, Claudel willfully demanded Rodin sign a contract she devised which included the following conditions: a promise to renounce other women, including favourite models and prospective students, to bring her along on his travels, and to marry her in 1887. In return she agreed to receive him in her studio four times a month. If Rodin did not meet the demands she set forth, the deal was off. He didn’t, so she called it off and renounced the male artistic master and all the trappings of success, public art commissions, and acclaim that he brought with him.

In her quest to find her independence and support herself as a woman artist, Claudel worked hard to secure a state commission for an ambitious sculptural group of three figures. The state commission was granted for her work titled L’Âge mûr (1902). The grouping features images of Claudel herself as L’implorante, a young nude woman beseeching a man (sculptor Auguste Rodin) to stay with her instead of being swept away by an older figure representing death. Auguste Rodin was at that time on the selection panel for French public art commissions, and because he found Claudel’s sculpture so threatening, her public art commission was suddenly cancelled. Claudel’s fight for the sculpture she believed in resulted in her being at odds with the artistic bureaucracy.

Claudel dug in her independent heels, and decided to embark upon a body of work dealing with interior emotions of women. Her works were unusually courageous for the time, candid in communicating emotional and physical pain, loneliness, and desire.

“My sister’s work, which gives it its unique interest, is that it is the whole story of her life.”

-Paul Claudel, poet and diplomat, brother of Camille Claudel

Claudel was a renegade in renouncing both social and artistic norms of her era. She was a renegade in that she created her own terms to live by, much like she created the unconventional contract she had Rodin sign.

1913: While Claudel herself was sent to spend the last 35 years of her life at a sanitarium due to her norm-defying behaviors, her insistence on doing things the way she deemed appropriate paved the way for women artists who came after her to do the same.

1939: Twenty-six years after Claudel’s family had her interned in a mental institution for her bold artistic actions and her outrageous act of choosing her artistic career over having a family, Judith Cohen, now known as Judy Chicago, was born in 1939 in the U.S. Like Claudel, Chicago was artistically talented from a young age, was fiercely independent, and pursued her artistic career with a vengeance. Also like Claudel, she was a renegade. She forsook the coldness of masculine conceptualism and the testosterone-driven assertions of dominance over the land by cutting into it, moving it; manipulating it, in favor of color and concept that were inherently true to her uniquely feminine perspective. Chicago embraced vulvic imagery and colors descriptively female, like pinks, purples, and other pastels. Her iconic collaborative work “The Dinner Party” was inclusive, rather than exclusive. She didn’t compete with women artists; she invited women from far and wide to become part of her artwork that highlighted the contributions of women throughout history. Today, Chicago’s “The Dinner Party” is considered the capolavoro of feminist art history.

1948: When Judy Chicago was nine years old and already taking the bus alone from her home in Chicago to the Chicago Art Institute for art classes, Hung Liu was born in Changchun, China. She came from a long lineage of intellectuals, and her father was an officer in the Nationalist army of Chiang Kai Sheck. Liu’s father was ultimately placed in a labor camp, where he spent the rest of his life. Liu and her mother burned all their family photographs that included him to escape retribution, and fled to Beijing. Liu was recognized very early in life for her extraordinary artistic talent. Because of her brilliance, she was placed in the top high school in Beijing, where Mao’s daughters also attended. There, Liu witnessed her principal be beaten to death by young woman zealots of the Red Army. She watched her math teacher jump to his death from the school grounds, and she saw her classmates beat another teacher to death with shoes, while he was belittled and forced to crawl on the ground in front of his students. Liu endured “re-education” during Mao’s imposed, eponymous Cultural Revolution, in which she was removed from school and forced to toil in the wheat fields in the Chinese countryside for 364 days per year. Though these times were undeniably tough for her, Liu’s determination to pursue her artistic career drove her. She hid a German camera and a watercolor set under her bed, and every day she took time to paint or to photograph her experiences. 35 of her “My Secret Freedom” watercolors are now in the permanent collection of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, and photographs she took with that German camera will be exhibited at her Smithsonian Institution’s National Portrait Gallery retrospective in 2021.

1984: When artist David Hockney visited China and the prestigious Central Academy of Art, where Hung Liu and other Chinese luminaries like Ai Wei Wei studied, he met “Ms. Liu” and was so impressed by her work and her countenance that he wrote about her artwork in his China Diary. Liu was determined to leave China for U.C. San Diego, to study contemporary American art movements like Happenings. She persisted in waiting four years–deferring her admission to UCSD each year while she waited–for the Chinese government to finally grant her a passport to pursue her artistic career. An only child, she left behind her mother, with her two year old son to care for, to pursue her artistic dreams. Since arriving in the U.S. in 1984, Liu’s artworks have been collected by more than 50 major museums in the country, from the Whitney Museum of American Art, to the L.A. County Museum.

1970-2010: Both Judy Chicago and Hung Liu dedicated a portion of their careers to teaching women artists to persevere and prosper, as well as sharing their network of dealers, curators, and art critic colleagues. Among the recipients of their shared wisdom were three artists that are making their own name for themselves in their own authentic voices today. Judy Chicago has adopted as her “radical daughter” the street artist known as Swoon, born Caledonia Dance Curry. Swoon regularly collaborates with Chicago on social activism projects like Create Art for Earth, joined by both Jane Fonda and über-curator Hans Ulrich Obrist of Serpentine Galleries in London. Swoon is renowned for inspiring an entire generation of female street artists, with her large scale humanistic wheat paste murals. Her works are now in major international museums such as the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the Tate Modern in London.

Hung Liu is the beloved mentor of artists Monica Lundy and Lien Truong, artists of Italian and Vietnamese progeny, respectively. Both artists have assumed the mantle of proselytizing for the disenfranchised in their artworks. Lundy uses traditionally female media like porcelain, coffee, and burned paper in her depictions of women who were incarcerated for being renegades. Crimes like being too loud, disobedient, or promiscuous landed these women in sanitoria, just as they had landed Camille Claudel in an asylum and silenced her artistic voice one hundred years earlier. Lien Truong singes antique silks and historic textiles blended with 22 k gold threads, and fuses exquisitely detailed abstract painting to tell the stories of racial and gender-based injustice.

New Mexico-based Agnes Martin, Raphaëlle Goethals, Karen Yank, and Jamie Brunson share a vision that is tied to the sanctity of the land. Rooted in the horizon line that is unfettered by vegetation, providing the feeling that one can see forever, these artists present the maverick notion that within simplicity of mother earth lies the most pristine experience of creative joy one can ever experience.

The women in this exhibition are indeed Renegades. They take the legacy of women artists and carry it forward into an apotheosis of success. Their manifesto is to be true to their uniquely female artistic vision, and they succeed beyond measure. Turner Carroll is proud to present this exhibition during Women’s History Month, honoring the contributions of women artists throughout history. Please join us in celebrating their accomplishments.

-Tonya Turner Carroll

Santa Fe, New Mexico

2021

Online Virtual Exhibition | Burned: Women and Fire

Etsuko Ichikawa: Making a Pyrograph

Special Judy Chicago exhibition and event to benefit Through the Flower

July 26, 2020 from 2-5 pm at Through the Flower Art Space in Belen, NM

Burned: Women and Fire

Artists include Judy Chicago, Monica Lundy, Karen Yank, Etsuko Ichikawa, Meridel Rubenstein, Jami Porter Lara, Julie Richard Crane, Hung Liu and Lien Truong.

Artwork in the exhibition may be viewed here.

Fire is one of the most potent symbols in human history. It purifies, illuminates, destroys, and transforms. “Mother Earth” has fire in its core. That magma—hot, molten rock—is an igneous rock. The name igneous comes from the word ignis, which means “fire” in Latin. This fire sporadically pushes its way through cracks in the earth’s crust and erupts from volcanoes, burning everything in its path to create a way for new life to emerge from the magma. Wildfires act in the same way, coming by surprise, expanding exponentially, and consuming fuel in its path, while simultaneously opening some types of seed pods for future growth.

The first civilizations in the Near East revered forces of nature and their enormous and only modestly predictable impact on daily life. Later, they would be personified as deities. Many ancient cultures saw fire as a supernatural force: Greeks maintained perpetual fires in front of their temples, Zoroastrians worshiped and regarded fire as pure wisdom that destroys chaos and ignorance, and Buddhist cultures practiced ritual cremation to purify the body upon its release from the physical world.

When early religions began transferring attributes of forces of nature to specific deities, many cultures equated fire rising from “Mother Earth” with archetypes of women. The Sumerian goddess Lilith had a fiery ability to control men. In Egypt, the serpent goddess Wadjet used fire like a snake spitting venom to burn her enemies. In the Philippines, Darago was the warrior goddess associated with volcanoes. Roman goddess Feronia was associated with the energy of reproduction and the fire beneath the earth’s crust. These ancient goddesses were fierce and powerful, and they used fire as their tool.

As male rulers took political, religious, and economic power through organized conflict, the diminution of women’s power was the result. Instead of depicting women as independent forces of nature, biblical authors described them pejoratively as harlots and sinners. These authors used fire to symbolize the guiding presence of God, and Abrahamic religions embraced the destructive power of fire as the wrath of God. In the Torah/Old Testament story of Eve, her bold pursuit of knowledge was as terrifying as a fiery natural disaster. When Eve was in the Garden of Eden she “saw that the tree was good for food…and a tree to be desired to make one wise, she took the fruit thereof, and did eat, and gave also unto her husband with her.” “The woman whom thou gavest to be with me, she gave me of the tree, and I did eat” Adam said, as he successfully blamed the woman for his choices and actions. The male God then cursed all women for Eve’s independent decision-making and disobedience: “I will greatly multiply thy sorrow…and thy husband…he shall rule over thee.”

Those words of condemnation, and words like them in other male-dominated institutions, attempted to change societal perception of women from personification of fire, and its natural ability to create and destroy, into the scorned embodiment of sin. Just as early Roman Christians built churches on top of pagan temples and later placed the orb and cross atop obelisks they looted from ancient Egypt, governments usurped female power by forcing a narrative of male moral, intellectual, and physical superiority. These institutions took archetypically “female” fire as their own symbol, using it as their weapon to control and limit women’s minds, bodies, and potential. Examples of this include doctors in pharaonic Egypt using fire to cure “hysteria” by forcing the uterus (hystera) upwards. Caught between the English and French monarchs, Joan of Arc was burned alive in 1431 despite being credited previously for the French victory at the Siege of Orleans. In early modern England, women were burned at the stake as a legal punishment for a range of activities including coining and mariticide. In 1652 in Smithfield, Prudence Lee confessed to having “been a very lewd liver, and much given to cursing and swearing, for which the Lord being offended with her, had suffered her to be brought to that untimely end.” She admitted to being jealous of and arguing with her husband. For this, she was burned at the stake, as were thousands of other women. In the late 1850s, The Industrial Revolution produced gauzy new fabrics that when made into funnel-shaped dresses, ignited instantly upon being touched by a spark. Their flammability made them death traps for women, preventing them from safely doing ordinary things men could do, such as lighting a match, standing close to a fire, or smoking a cigarette, lest they be burned alive.

Tragically, women are still burned to death by men today. In New Zealand in 2011, a groom doused his bride with flammable liquid, set her on fire, and left her by the side of the road to die so he could obtain a higher dowry from another. In 2015 in New Guinea, four women were tortured and burned for sorcery. Acid-burning is at an all-time high, occurring from the United Kingdom to Southeast Asia. In India and Pakistan, widows are sometimes burned with their deceased husbands in his funeral pyre, and the highly suspect “kitchen fire” is all too common. In contemporary honor killings, families burn their own daughters and sisters for making unapproved decisions about their own marriage. The United Nations estimates that as many as 5000 women are killed annually world-wide in honor killings. Today, this act is not illegal in such modern nations as Jordan.

It is no wonder the element of fire is ingrained in women’s collective memory. Fire represents women’s power and their torture. In women’s own hands, it is their independent creative spark; in the hands of those who want to suppress them it can destroy their very lives. Burned: Women and Fire features artists who—like the alchemical Phoenix who burns and rises from the ashes anew—integrate their collective experience with fire and burning to create their art.

Tonya Turner Carroll

Santa Fe

January 2020

“Karen Yank and Agnes Martin” in the Albuquerque Journal

We received a great review for this exhibition. In the October 7, 2018 edition of the Albuquerque Journal, Wesley Pulkka writes “For Yank the iconic show emblemizes the end of the beginning of her career that really took off in 1987 when Yank met Martin at the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture in Maine. The two women formed a friendship and mutual aesthetic understanding that grew and solidified over the following 17 years until Martin’s death. Martin considered Yank to be her only true student.”

A link to our exhibition is here. A copy of the article is here.

8 October 2018

September 21 – October 15, 2018 | Karen Yank and Agnes Martin

Opening Reception Friday, September 21, 5-7pm

This exhibition is extremely significant and personal. Simultaneous with an upcoming book project on Agnes Martin’s artistic and life philosophy, titled Travels with Agnes, Yank and Turner Carroll present an exhibition that reveals visual relationships between one of New Mexico’s most well-known contemporary artists—Agnes Martin, and the student she mentored for the last 17 years of her life—New Mexico sculptor Karen Yank.

Agnes and Karen met in 1987 at Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, in Maine. They met at a critical time in both of their lives. Yank had just graduated from art school, beginning her artistic career. Martin was at the end of her teaching career, and chose Yank as the human receptacle for her philosophies about art and living. She regarded Karen Yank as her “true student” on a profound philosophical level. As in John Steinbeck’s Travels with Charley, Martin had taken off in her truck, driving all over the U.S., ultimately choosing New Mexico as her home. Yank had chosen New Mexico as home, as well. Martin and Yank continued their close friend and mentor relationship after their return from Skowhegan to New Mexico, for the remainder of Agnes Martin’s life.

Martin unabashedly advised Yank on her sculptural works. She reminded Yank that “we are unfolding flowers. We need to listen to life and let life tell us what is next, relinquishing control and opening ourselves to true inspiration.” In the early years of Yank’s career as an artist, Martin rejected the circle as “too expansive” because Martin, herself, had not been drawn to it as a vehicle for her own inspiration. One of the greatest insights in both Martin’s and Yank’s artistic development was Martin’s response to Yank’s circular, banded discs, created from steel in the late 1990s. Martin amazed both Yank and herself by declaring these circular shapes “Yank’s vision and her mature voice” in her art. Martin said the circle was an obviously good choice for Yank and not for her, because Yank’s use of metal made the circular works more object oriented than illusional. The expansiveness of the circular shaped sculptures helped reverse their object-ness and enable the viewer to enter into the various planes and energetic fields of the works.

Agnes Martin also shared much of her wisdom about how an artist could best conduct daily life. She pointed out to Yank some decisions she had made in her life that she later regretted. Some of the decisions Martin regretted are surprising, like her famous choice to cut herself off from society and live an isolated, solitary life. She encouraged Yank to fully engage, only pulling back from the outside world when she was deeply inspired to create her work, and then to partake again in the social life.

Toward the end of Agnes Martin’s life, she asked Yank to keep Martin’s artistic philosophies alive by conveying her teachings to younger artists. She believed Yank could continue her admonitions to younger artists to remain true to their artistic convictions and allow themselves to mature and unfold. She believed artists have to find meditative purity in their artistic practice, to achieve the peace and solid framework for their works. Martin wanted Yank to teach young artists generously, as she had taught Yank, as she grew from young to senior artist.

Yank has let Martin’s teachings ruminate in her mind since Martin’s death over a decade ago. She seen other books emerge about Martin, and she sees that Martin’s teachings have not yet emerged. She now feels like it’s not her choice, but her duty to her friend and mentor, to preserve Martin’s philosophies of art and life so other artists can benefit from her as she did.

Over the 17 years Martin and Yank spent together, Martin taught Yank to notice the small details of life, and to strive for contentment in every moment. “In my life Agnes and I had a unique relationship. May she live on through her paintings, her teachings, and those who truly understand her genius.”

Work in the exhibition may be viewed here.

For more information and high resolution images, please visit https://turnercarrollgallery.com/press-area/ or info@turnercarrollgallery.com

Karen Yank Monumental Sculpture Installation at CNM, Albuquerque, New Mexico

Dedication Ceremony

October 10, 2017

3:00-3:30 p.m.

West of Student Resource Center (SRC)

Lecture & Reception (Comments by Art Historians Tonya Turner Carroll and Wesley Pulkka)

October 10, 2017

5:30 – 7:30 p.m.

Jeanette Stromberg Library, SRC

“Growing Strength” Installation

The monumental sculpture commemorating CNM’s first 50 years is nearing completion. The expansive three-piece sculptural group stands in the xeriscape garden west of the Student Resource Center (SRC). Two benches, fabricated by CNM welding students, will face the large work from the shade of spreading elms across the walkway, and provide a comfortable place to relax and enjoy the view.

“Growing Strength” was commissioned from artist Karen Yank, known for her large-scale, steel-ornamented public sculptures and her award-winning freeway interchange designs in Albuquerque. Yank, a widely exhibited and nationally recognized sculptor, has works in cities and prestigious public collections across the United States. She works in welded steel construction, taking full advantage of the characteristics of the material and pushing the limits of the medium to construct dynamic and imaginatively engaging works. She is currently represented by Turner-Carroll Gallery in Santa Fe.

The work echoes and plays off of design motifs in the SRC, which provides a contrasting architectural backdrop. “The sculpture is abstract, combining elements of a mountain topped by a wildflower growing out of a fractured rock. The flower has a petal that drops to the ground, flowing into a bench seat,” Yank said. “The mountain is a metaphor for CNM’s strength and stability and how the college has grown, and the flower represents CNM’s fruits of labor and what the school gives back to the community.”

The delicate flower also symbolizes the qualities of growth through the learning process. The shape of the entire piece contains curves and angles that are in some places fluid and graceful and in others jarring and awkward. The complete picture is one of wholeness, intention and fulfillment.

“The sculpture is designed specifically to embody CNM’s mission and values and was created for this particular location, but it also expresses the strength and vitality of Karen’s maturing artistic expression” said Mary Bates-Ulibarri, project director and CNM Libraries branch manager. “The piece is connected to the SRC, and it is intended to be a centerpiece for the Main Campus, just as the SRC is the hub of student learning. We are fortunate to have what is sure to become an important piece in Karen’s body of work.”

“The design of my art expresses a context that can be understood in a moment but with layers that can be seen by those who pause to look deeper,” Yank explains. “My overall goal is to develop a visual language that is compelling within the given environment and community.”

The artist was selected through a very competitive, formal juried selection process, organized by Arts in Public Places, under the New Mexico Division of Cultural Affairs. She was among six finalists, selected from approximately 200 applicants from all over the United States. The selection committee was comprised of faculty, staff and student representatives, who brought different expertise and diverse cultural and professional perspectives.

“The committee chose Karen based on the strength of her past works, the quality of the proposed work, how well it matched the criteria of the committee’s prospectus, and her willingness and ability to engage the CNM community,” Bates-Ulibarri said.

Fabrication and installation of “Growing Strength” was a collaboration between the artist and Damon Chefchis, owner of CMY, Inc., a custom metal fabrication shop in Albuquerque’s South Valley. The two bench seats across the walkway were fabricated by CNM welding students under the direction of Welding Department Chair, Kay Hamby, welding instructors Ron Hackney and Trent Moore, with the assistance of Welding Technician Jasen Thomas, “From the beginning, we developed the intention of involving CNM students as much as possible, in the spirit of the Campus as a Living Lab initiative,” recalls Bates-Ulibarri. The artist and fabricator also invited CNM students to view the work in progress at CMY’s shop, offering insight into the process of designing and constructing a large-scale work, and the importance of planning, teamwork and communication required to succeed in such a venture.

The project is funded by the “One Percent for Art Program,” managed by Arts in Public Places (AIPP), a division of the New Mexico Department of Cultural Affairs. The budget for “Growing Strength” was $112,750, which included the artist’s fee, materials, labor, sales taxes, licenses, permits and inspections, site preparation and site restoration. The project was attached to the construction of the SRC.

An article in the Albuquerque Journal on the artwork and Karen Yank and her artistic path is here.

March 8 – 31, 2017 | Matri-ART-y: Women’s’ March on Art!

Squeak Carnwath

In a civilization where more than 51% of the population is female, yet 96% of exhibition space is given to men, it’s time for a change. In honor of National Women’s History Month and in celebration of uniquely brilliant female perspective, Turner Carroll features important women artists all month. Artists include an international roster including Nina Tichava, Raphaelle Goethals, Hung Liu, Squeak Carnwath, Karen Yank, Jamie Brunson, Mavis McClure, Jenny Abell, Suzanne Sbarge, Holly Roberts, and Brenda Zappitell.

Opening Reception Friday, March 10, 2017 from 5 to 7pm

[n.b. that this event takes place in Santa Fe]

July 19 – August 9, 2016 | Drew Tal and Karen Yank: Circumspect

Circumspect

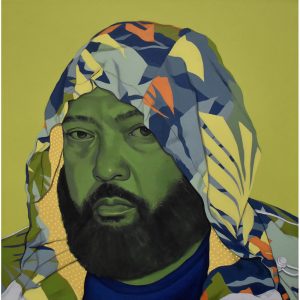

Agnes Martin once told Karen Yank that the “circle is too expansive” as an art form. Karen later said it was perfect shape for her, because she could control it; because she understood its implications. In the same way Drew Tal uses the gaze on the circle of the face and the eyes to make a comparison of universal features.

Opening Reception Friday, July 22, 2016 from 5 to 7pm

[n.b. that this event takes place in Santa Fe]

July 3, 2016 | Drew Tal and Karen Yank: Circumspect

Drew Tal

Circumspection implies considering your actions carefully before moving forward. Such is the case with both American artist Karen Yank, and Israeli artist, Drew Tal. Yank was awarded a prestigious art award to study at Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture in New York, in 1987. Her teacher was the celebrated–if reclusive–New Mexico minimalist artist, Agnes Martin. Yank relocated with her family to New Mexico, where she still lives today. Her friendship with Agnes Martin would continue for two decades, until Martin’s death in 2004.

Agnes Martin often told Yank she was her only “real” student. She passed on her opinions about artistic process and philosophy to Yank. While Martin is well known for her grid drawings and line paintings, Yank sought a different shape. Martin’s horizontal line was reminiscent of the distant New Mexican horizon line, uninterrupted by natural form. Yank, however, saw the circle as the most perfect shape for her sculpture. From earliest civilization, the circle has represented the life-giving force of the sun; eternity; fertility, divinity. Yank created a large body of work using the circle, often with referencing Martin in her use of the line within her circles, as is evident in her piece called “Thrice” as well as in her “XO” series.

For Drew Tal, his environment produced circumspection, as he states, “Growing up in Israel in the ’60’s, was a blessing for me. At that time in history the young state was a true melting pot for millions of immigrants from all around the globe. Surrounded with such a colorful collage of ethnicities, languages, nationalities, cultures and religions made me realize from an early age that the world beyond me was a rich and complex place. This revelation opened my eyes to the exotic, and made me extremely curious about people and their religions, customs, costumes and histories.”

While Israel has experienced much political strife during Tal’s lifetime, he regards each human being as equally sacred, regardless of ethnicity or religion.

April 14 – 17, 2016 | Turner Carroll at the Dallas Art Fair

Dallas Art Fair

Located at the Fashion Industry Gallery, adjacent to the Dallas Museum of Art in the revitalized downtown arts district. Featuring new works by gallery artists Fausto Fernandez, Hung Liu, Squeak Carnwath, Drew Tal, Jamie Brunson, Rusty Scruby, Edward Lentsch, Wanxin Zhang, Suzanne Sbarge, Karen Yank, Scott Greene, Holly Roberts, and more! Fair hours are Friday and Saturday, April 15 and 16 respectively, from 11am to 7pm, and Sunday, April 17 from 12pm to 6pm, with an opening preview gala Thursday, April 14.

A link to the Dallas Art Fair is here.

Facebook Post Artist Karen Yank and Damon Chefchis 20 November 2017

Artist Karen Yank and Damon Chefchis, fabricator and owner of CMY, Inc, giving a public presentation this morning on the large scale metal sculpture that they’re making for CNM. It was a great turnout with lots of CNM art students in attendance!