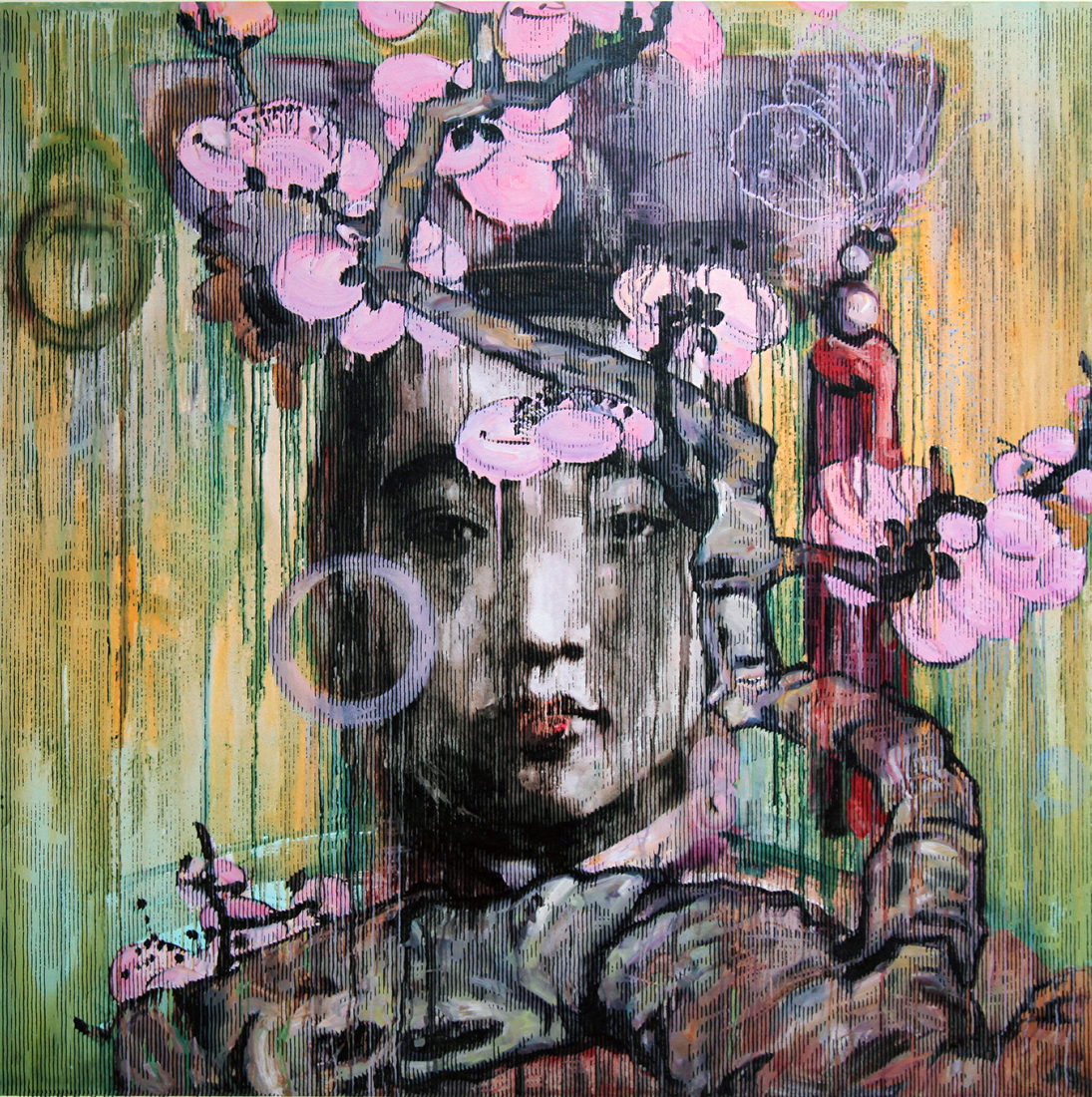

Artwork Description

Hung Liu – Winter Blossom

Dimensions: 32.25 x 29.75″ framed / 32.25 x 29.75″ framed

Year: 2011

Medium: woodblock with acrylic ink on paper

Edition: 25/25

To quote the master printers who worked with Hung Liu in creating this print (Don Farnsworth and his staff):

The face wreathed by plum blossoms and crowned with a tasseled headress in Winter Blossom belongs to Imperial Concubine Zhen Fei, popularly known as “the Pearl Concubine,” who died in 1900 at the age of 24.

A lively and independent woman, Zhen was the favorite consort of the Guangxu Emperor, and encouraged his attempts at reform and his interest in foreign languages. The story goes that Zhen also invited foreigners into the Forbidden City to indulge her interest in photography, which explains the extant photographs of Zhen – unusual for an Imperial Consort (and, according to Hung Liu, mostly faked).

Unfortunately, Emperor Guangxu’s modernizing attempts to reform China angered the country’s de facto ruler, Empress Dowager Cixi. When it was revealed that Zhen had supported the Emperor’s coup attempt against the Empress in 1898, Zhen was imprisoned.

Two years later, as the Court fled an invasion of the Forbidden City, Zhen was summoned from prison to meet with Cixi. In a move of backhanded concern, the Empress Dowager ordered that the Pearl Concubine throw herself down a well behind the palace, rather than suffer the fate awaiting her at the hands of invading soldiers. The story is especially unreliable after this point; no one can say for sure how Zhen passed – only that she died during the invasion.

As with the many colorful figures from this period to appear in Liu’s work, the historical record of Zhen’s life and death is not necessarily to be trusted; over time, legendary tales have assumed the veneer of truth, and many dubious photographs have appeared posthumously. It is fitting, then, that Liu would combine two media to create a print with a shifting surface, wherein Zhen’s face is seen as an apparition, partially masked by the black lines of the woodcut.

In fact, Liu based her print on a photograph which historians agree is the actual Zhen – although here again, things are not quite what they seem. “She looks very beautiful,” the artist told me, “but the photo is very highly touched up, almost artificially rendered, to the point that it has become a surreal image.” Liu added: “Her tragic life makes it even more mysterious.”

The artist’s sympathy for this unique and forward-thinking young woman is evident throughout Winter Blossom‘s composition. The ghostly trace of a butterfly sits atop the red tassel on Zhen’s headdress (such tassels indicated one’s rank in the Imperial court). The branches which encircle her face, Liu explains, are “a certain kind of plum that blossoms in the cold, with flowers like translucent wax.” These plum blossoms symbolize both a resilience against the cold and a tragic evanescence. “I offer this image,” says Liu, “as a tribute to a short-lived woman about whom we still know very little.”